Empathy as an Intellectual Tool: Prof. Ben Scribner on JCU’s New Gender Studies Course

Ben Scribner, who joined JCU in 2014, holds an M.A. in Sociology from the University of Oregon and a doctoral degree in Communications from La Sapienza University of Rome. His thesis concerned representation and the construction of national space in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Professor Scribner teaches Intercultural Communications and the soon to be launched course, Introduction to Gender Studies.

Prof. Scribner was recently interviewed by JCU’s Director of Web Communications, Berenice Cocciolillo.

Tell us something about your background. What brought you to Rome and JCU?

I grew up in New Mexico and Oklahoma in the 70s and 80s in a conservative environment. When I turned 20 I dropped out of college and ran off with my best friend to San Francisco to play in a band. I gave up on the band before we had time to get famous (haha), but the city exposed me to communities, individuals, and lots of ideas that my previous life had more or less “protected” me from. Motivated, I went back to school, studied sociology and economics, became active on a number of issues and taught. In 2002 I met my partner, who is a biologist from Rome, and eventually followed her here. I got my Ph.D. in Communications while being a stay at home dad and acclimating to Italian culture. Long story short, I could never have dreamed of ending up in Rome, but this is the first place I have felt settled since leaving home back in 1992. I guess having a child will do that to you, but finding an academic home at JCU has been a big part of it also. I love teaching and am glad that it continues to be a big part of my life.

What are your current projects?

I´m converting my doctoral thesis on Israeli settlements into an article which should be published soon, and I am studying up and reading for the Intro to Gender Studies course in the Fall (it’s version 1.0!) as well as revising my Intercultural Communication course.

What is it like to teach Intercultural Communications to an international student body such as the one at JCU?

Yes, of course, JCU has this amazing dynamic of visiting students and year-round students, and both of these groups are also very diverse within themselves. I find it 100% positive in the classroom. The challenge for me is to foster an atmosphere where we give due weight to every single person’s ideas and experience while maintaining unity as a class. Experiences are different but when it really works people are laughing about the differences alongside the serious stuff, or opening their eyes wide because they can’t believe what they just heard, but ultimately respecting it. I am someone who tends to want an orderly class but ironically my favorite moments are when it goes totally out of my control in a positive way. That’s not just a basis for intellectual work but also for friendships to form between the students. It makes me very happy when I see intercultural friendships coming out of the classes.

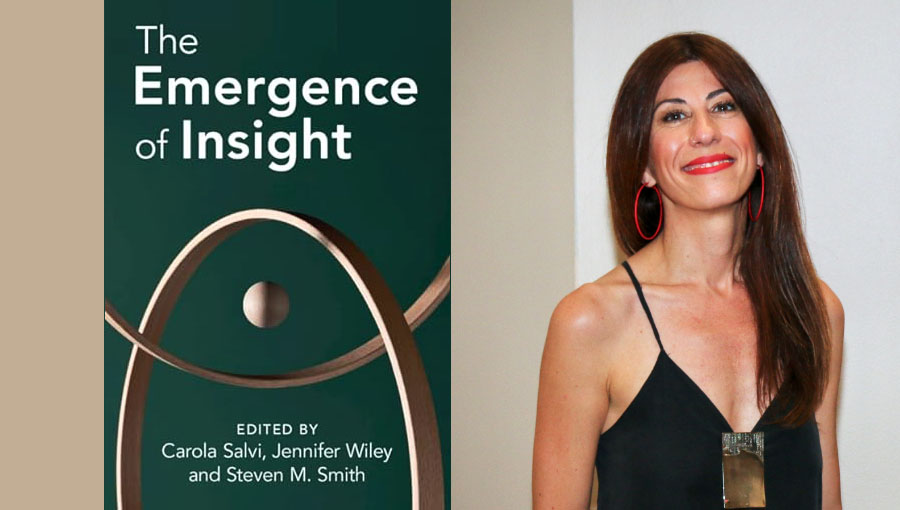

Professor Ben Scribner

Tell us about the new Introduction to Gender Studies course (SOSC/GDR 200) that you will be teaching in Fall 2020. What is the main thing that you hope students will take away from the course?

I want them to take away the idea that empathy and curiosity toward people with different experiences than our own are necessary for intellectual growth. The discipline of Gender Studies tells us that each of us sits at the intersection of privileges and oppressions around gender, race, class, nationality, sexuality, and so on. Some of us are in a better position to see how it all works while others….well, you simply can’t see what’s going on if it doesn’t happen to you. It is rare to talk about privilege as a disadvantage but following from the scholarship, I am convinced that the experience of privilege makes us ignorant in very important ways, while oppression reveals truths about the nature of things. As Patricia Hill Collins said, oppression is rarely pure, so each of us has to counteract the intellectual disadvantage that accompanies our particular mix of privileges. We can do that by listening to those with different experiences. Gender theory helps each of us to identify the voices that are being kept at the margins of our consciousness so we can bring them to the center and listen, and actually motivates us to do so.

How would you describe your teaching methodology?

I do the usual thing of assigning readings, introducing theories and exercises from the academic sources that are fundamental to getting it all going; in this case, we are talking about scholars of masculinity, feminist theory, queer theory, intersectionality, the sociological history of gender relations and so forth. But most of all I urge students to create something worthwhile and memorable through meaningful academic discussion. In any classroom, there are lifetimes of experiences and ideas to share and process, let alone our ongoing lives and situations. We set up these intellectual categories like “masculine” and identities like “gay” but there is no single experience that represents either of these. Whether a student says “I want to share an idea” or “I am ignorant about this, can you explain?” they are giving a valued gift to their peers by opening up. I say gift because I cannot require nor do I pressure students to discuss things they don’t want to discuss. It is up to them to decide if they want to take the risk (and reap the reward!). But when they do, that becomes the real material of the course. At the end of the semester, students remember what I said because it was on the exam, but they remember what their peers said because it was real to them in a way it can’t be when it comes from me. A lot of this also happens in writing assignments as well, where students sometimes feel more comfortable reflecting and sounding out new ideas.

What kinds of challenges do you foresee in teaching the Gender Studies course?”

This course will be a huge challenge but I am excited about it and confident about my ability to engage the students in the way I described above. But to answer on a more personal level, I am reflecting a lot on these days on my responsibilities as an ally and my role in teaching a course like Introduction to Gender Studies. As I discussed above, I think my own layers of privilege put me, as a white heterosexual cisgender man, at a disadvantage in intrinsically understanding the forms of oppression that are typically focused on in such a course. I know that I can try to model the critical reflection that I am asking of my students, but that only goes so far. My “solution” is to teach the material with the passion it deserves knowing that people live and die around these issues, and put the voices of those whose experiences are typically marginalized directly at the center of the discussion via the course materials, and above all create as safe a space as possible for those with different experiences than my own who are in the classroom with me (I mean safety in terms of human respect, not intellectual safety). That said, I recognize that what I can do is simply not the same as a class led by a professor who can make intellectual use of the experience of oppression and bring it to bear on the discussions, even by the mere power of presence. Such voices should be lifted up and such presences should be more often felt, especially in teaching roles like this one. So I know that the time may come where I need to step aside from teaching this particular course. In the meantime, I will do what I can to stretch the limits of what I can achieve through hard work, empathy, and compassion.