Italy Reads: Professor Antonio Lopez on Rachel Carson's Silent Spring

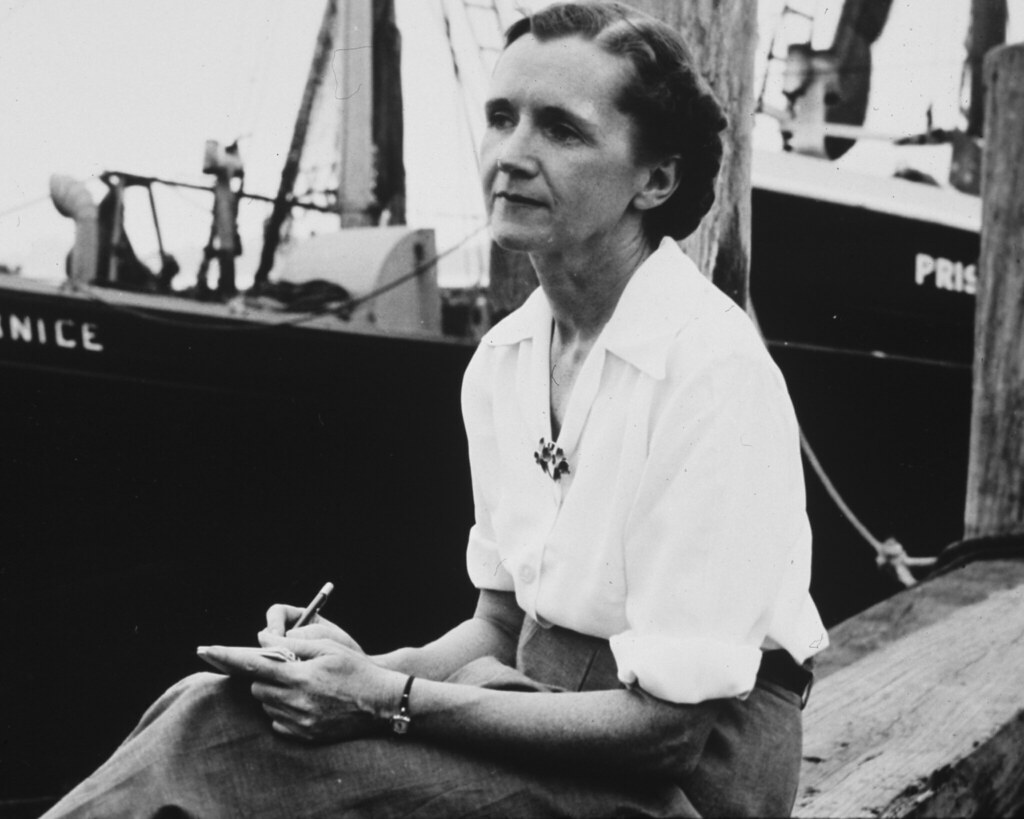

On October 14, John Cabot’s Italy Reads program hosted JCU Department Chair and Associate Professor of Communications and Media Studies, Antonio Lopez, who presented Silent Spring in 2020: What Rachel Carson Teaches Us About COVID-19 and the Climate Crisis. The event provided an analysis of the current climate situation through the works of American biologist Rachel Carson (1907-1964).

One of Carson’s best-known works, Silent Spring (1962) is a book that documents the detrimental effects that the indiscriminate use of pesticides has on the environment. Carson accused the chemical industry of spreading disinformation, and public officials of accepting the industry’s marketing claims unquestioningly. The main theme of Silent Spring is how humans are part of the web of life and that chemicals in the environment impact humans and non-humans alike. The book had a powerful impact on environmental movements, leading to a campaign to ban the use of DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) in the United States, and to the creation of the Environmental Defense Fund in 1967. It spurred a reversal in the United States’ national pesticide policy, led to a nationwide ban on DDT for agricultural uses, and helped to inspire an environmental movement that led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Professor Lopez introduced Silent Spring and defined it as a cultural and moral project that revolves around a simple but fundamental question: do humans have the right to control nature? “Carson’s book altered the power dynamic between the chemical industry and the public, and it’s hard for a book to do that,” said Lopez, describing the impact that Carson’s work had on society.

Problems don’t exist until they are named

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, was an international treaty signed in 1987 designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion.

Professor Lopez showed a picture of the Ozone hole, explaining that it is not an actual “hole.” However, in order for people and governments to take action and ban CFCs (Chlorofluorocarbons) in 1987, the image of an ozone “hole” was produced to raise awareness. “According to social constructivism, an environmental problem doesn’t exist until it is discursively created,” Professor Lopez said when introducing the importance of language to identify environmental disasters.

How Carson named the problem

After World War II, science and chemistry were perceived as signs of civilization and technological progress. In the 1940s, pesticides became a “conventional” farming practice and DDT was promoted as a cure against malaria and typhus. Professor Lopez showed the audience a black and white photo of an Italian woman being covered in DDT to cure her of typhus during an epidemic in Naples at the time of the US military occupation in WWII. However, exposure to chemicals such as DDT, as Carson explains, could alter the structure of genes and cause cancer. This is why she addressed pesticide as “biocide,” underlining once again that the chemicals do not only kill insects but destroy life in general. DDT was banned in the US in 1972, ten years after the publication of Silent Spring, but not everywhere.

Environmental problems still persist

According to scientists, we are currently living in what is defined as the sixth mass extinction caused by human behavior. Five hundred species of land animals are on the brink of extinction and could be lost in 20 years. We already lost half of the global wildlife in the last 40 years, including a decline in the bird population that looks even more dramatic considering the disappearance in 50 years of 3 billion birds in North America. 80 percent of the insect population has disappeared in 25-30 years. Lopez explained that we should be careful because the extinction of insects could lead to the collapse of ecosystems: birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insect-eating fish will starve without them. Moreover, insects pollinate plants, keep the soil healthy, recycle nutrients, and control pests, so the food chain could be destroyed. However, toxic chemicals continue to be used, as well as newer and deadlier pesticides.

COVID as environmental crisis and Carson’s legacy

Practices such as extractivism, deforestation, monocultural agriculture, and the use of chemicals created opportunities for the coronavirus to enter the human population and spread. Yet, the virus is still treated as a societal problem, as opposed to an environmental one. Carson demonstrated that environmental and social issues are interrelated and that we need a holistic approach in order to solve them.

The spread of Coronavirus shows how important it is to continue Rachel Carson’s legacy by rejecting the idea that humans should control nature, denouncing industrial and technological malpractice, and bringing awareness to the food chain’s interdependence. This can be done by reducing or eliminating synthetic pesticides, transitioning to non-industrial forms of agriculture, making parks and gardens more wildlife-friendly, preventing deforestation, promoting reforestation, and “re-wilding” vast areas of the earth.

Professor Lopez closed the event by citing Rachel Carson: “Man’s endeavors to control nature by his powers to alter and to destroy would inevitably evolve into war against himself, a war he would lose unless he came to terms with nature.”