Professor Lila Yawn on the Fifth Anniversary of the M.A. in Art History

Lila Yawn, Director of the M.A. in Art History, holds a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and specializes in the history of medieval art in Italy. Professor Yawn also serves as an Advisor of the American Academy in Rome, where she was a Rome Prize Fellow in 1996-1998.

Professor Yawn was recently interviewed by JCU’s Director of Web Communications Berenice Cocciolillo.

Congratulations on the fifth anniversary of the M.A. in Art History! Tell us about how the program came to be.

Ten years ago, President Franco Pavoncello asked the Department of Art History and Studio Art to propose an M.A. curriculum in Art History. We were elated but also stunned. Designing a master’s from scratch is a rare privilege but also a huge challenge and responsibility. The stakes were especially high, given that it was to be the University’s first graduate degree program, as well as the first M.A. in Art History taught entirely at a US-accredited institution in Rome. There was no template for it. Everything had to be created from scratch.

We spent several years researching, looking at the best M.A. programs worldwide, and working very hard to come up with a structure that made optimal use of our two biggest assets: the University’s enviable location, and the internal diversity of the department. The research specializations and teaching competencies of our faculty run the gamut from classical antiquity to contemporary, with everything in the middle covered. That range is rare in US art history programs in Italy, and the curriculum we designed takes full advantage of it.

What else makes the program special?

The first, most obvious answer is that we are in Rome. That’s a fabulous advantage for the simple reason that we can use one of the most art-historically rich cities in the world as classroom, as a venue for research, and as a base for study excursions all over Italy and Europe. Rome is packed not only with important museums and monuments but also with immense quantities of unpublished artistic and archival material. Over the course of the M.A., students build up research experience through seminar projects and theses on a wide variety of topics, including objects and documents that have been studied little or not at all. That’s one of the things we train people to do, and in Rome, and in Italy in general, the possibilities for such projects are endless.

Tell us about the faculty.

The professors who teach for the M.A. are simply tops. I feel incredibly lucky to have such brilliant, dedicated colleagues. Most of us live in Rome because our research is centered here. We’re really plugged into the Italian context and tap into our resources and networks to make the program challenging and intellectually rich for the students, as well as for ourselves. That’s what graduate study at its best is about: a group of advanced students and professors working together to become better thinkers, researchers, and communicators. We’ve built a vibrant intellectual community, which includes not only current M.A. students but alumni, as well. They tend to stay in touch.

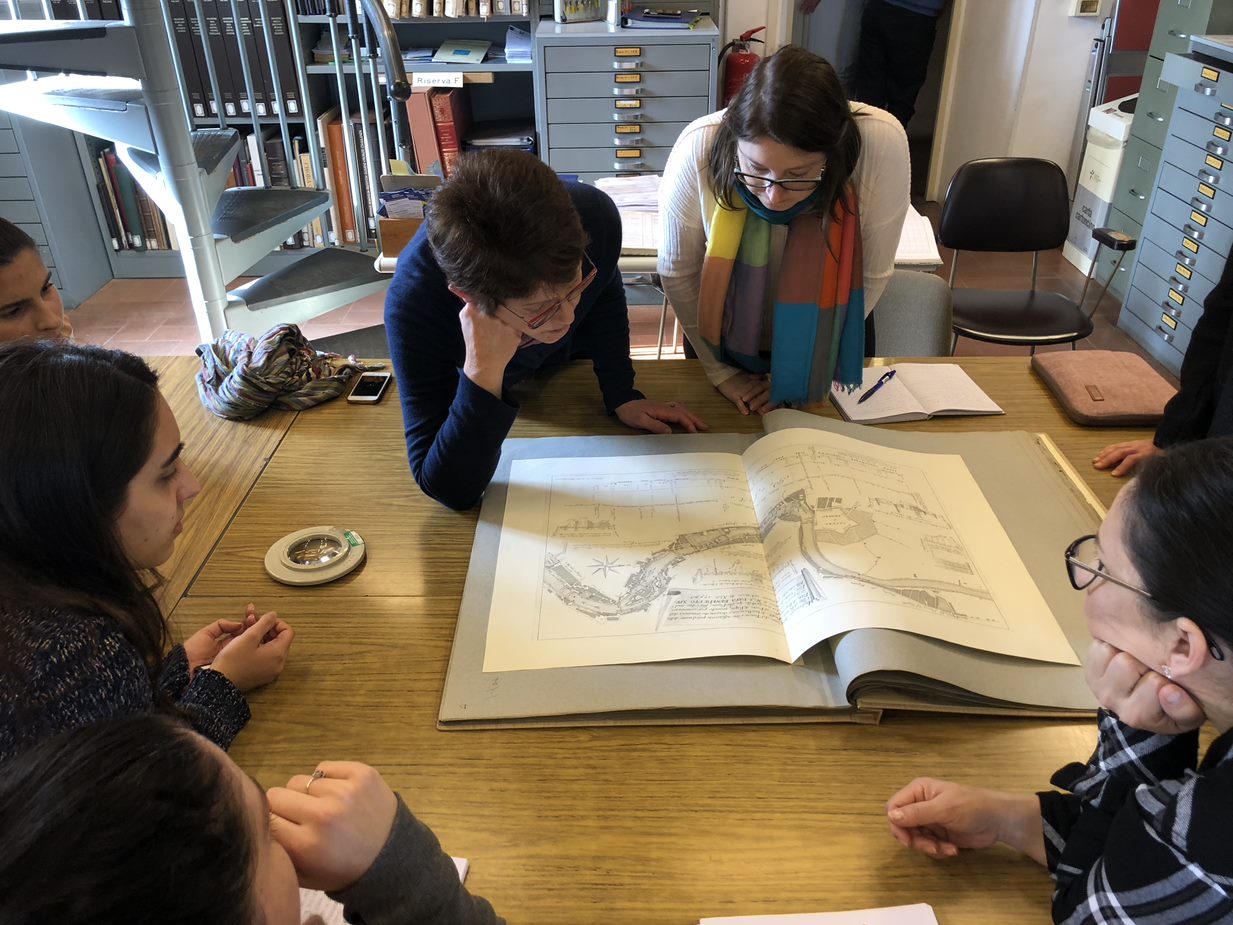

Professor Lila Yawn (left) visiting an archive with students

Tell us about the Professional Experience component of the degree.

It’s one of the crowning glories of the program. We have professors dedicated to identifying and facilitating internships for M.A. students directly pertinent to their interests and professional aspirations. Lately, students have interned at some of the most interesting museums and repositories of art in Rome, including the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica and the Museo delle Civiltà, which just made headlines for its state-of-the-art reorganization and reinstallation. Another sought-after option is serving as a teaching intern—it’s a super experience—or doing research or archival work for a gallery, think tank, or cultural institute, such as ARCA, The Association for Research into Crimes against Art. Occasionally the PE takes the form of an independent project. In the past, M.A. students have developed art-historical websites, walking tours, research archives, informational videos, and more.

The skills and contacts gained through this component often parlay into other professional experiences and in some cases lead to jobs. Our graduates are now running art centers, working at important museums and galleries, teaching at community colleges, and managing the studios of contemporary artists. It’s gratifying, especially considering how new the program is. One alumna started her own cultural tourism business. Another is a successful independent curator. Yet another is an art vlogger with thousands of followers on social media. Many alumni have gone on to further graduate work, either toward Ph.D.s or M.A.s in parallel fields, at very interesting institutions: the University of Chicago, the University of Bath, the Central European University in Vienna, the Centro Alti Studi in Lucca, The Catholic University of Portugal in Lisbon…

How would you describe the atmosphere of the program?

It’s rigorous—the students work very hard, and so do we—but it’s also wonderfully collegial and very human. As program director, I consider it a sacred duty to foster a community of mutually supportive scholars. The professors follow student work closely and help people find their intellectual grooves. The students, in turn, often form close friendships with one another. Graduates from five years ago are still collaborating on projects, communicating regularly, sharing ideas and their professional networks, going to conferences together.

What are your biggest challenges as Director?

Keeping it all together! I often feel like a juggler trying to keep a hundred balls in the air at once. It’s exhausting but joyous. One big challenge is helping students make the transition from undergraduate to graduate study. The intensity really takes some people by surprise, but nearly all students rise to the occasion and leave the program transformed as thinkers and professionals. You can really see it at the end of the Fall semester when M.A. candidates on the verge of graduating present their theses at a public colloquium in our Aula Magna. The papers are always impressive and often ‘conference ready.’ Several students have gone on to present their research at major scholarly conferences and to publish in the conference proceedings.

Another big challenge is that the M.A. is still something of a well-kept secret. Perhaps because our program is genuinely like no other, it’s surprisingly hard to get the word out that we exist and to let the world know what amazing things our students and graduates are doing. Communicating how vibrant it is could really be a job unto itself. So much is going on at any given moment, between site visits and field trips, meetings with museum directors, artists, and craftspeople, students giving conference papers, writing highly original theses. I often feel like we need our own full-time publicist.

Professor Lila Yawn

What are your hopes for the future of the program?

After it was launched in 2017, the M.A. has grown by leaps and bounds. The first class had eight students. Then in 2019-2020, the number tripled, Since then, that number has remained roughly constant, apart from a slightly smaller entering class in 2021, due to the pandemic. To date, fifty students have graduated, if you count those submitting their theses right now. That number seems poetic, since it coincides with the University’s fiftieth anniversary and the fifth birthday of the program. One of my hopes is to maintain that level of critical mass with highly qualified students while continuing to diversify the student body. We’ve had students from all over the world—Italy, the US, Canada, Turkey, Romania, South Sudan, Hungary, Nicaragua, Ukraine, Cyprus, Russia, Japan… I would like to see that list grow further.

Another aim is to enrich the array of courses and internships even further and to develop more venues for student publications. Their work, even in first-year seminars, is often groundbreaking, first-hand work from the primary record. It’s the kind of research one normally begins to do at the Ph.D. level. Speaking of Ph.D.s, am I allowed to say that one of my secret dreams (and not only mine) is to launch a doctoral program in art history one day? But please don’t tell.

What do you think of students who are deciding against studying liberal arts in favor of STEM subjects?

Many of our M.A. in Art History graduates are gainfully employed in the field. Are they making as much money as electrical engineers? Maybe not (for now). But if they love art history and the art world and are making a living in the sector, is money really the most important thing? Work takes up so much of one’s life. Graduate work in any field is ultimately not about getting a job, although in art history an advanced degree is required for most entry-level positions. Rather, it’s about making a quantum leap to a higher intellectual and professional level by mastering a field of knowledge (or darn well trying) and greatly improving and exercising your capacities for research, writing, and critical and creative thought. Graduate study tests your mettle and builds your productivity like nothing else.

To people outside the discipline, ‘art history’ may sound fluffy and elitist, like something privileged people do for fun in their spare time, but nothing could be further from the truth.

For art historians, human-made objects are points of departure for deep inquiry into how people of the past (including the very recent past, for contemporary specialists) thought, saw, traded, communicated, and cooperated; what they considered useful and beautiful; how they lived, interacted, worked, structured their lives, used and abused each other, the planet, and other species. The discipline is fundamentally mind-opening: a form of time travel—a skill STEM people haven’t yet mastered—and a way to connect with people whose realities were often unimaginably different from ours.

What art historians do is also important for the here and now. Our world is immersed, even drowning, in images and material things that are socially operative in powerful ways, including in national and world politics. Well-trained art historians are acutely good at parsing and interpreting pictures and objects, at teasing out their meanings, and seeing through their fallacies. If you think art history is frivolous, try taking one of our courses.