Professor Will Schutt Wins Prestigious Poetry Translation Prize

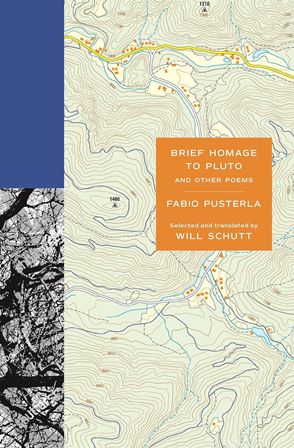

JCU Creative Writing professor Will Schutt has won the Joseph Tusiani Italian Translation Prize for his translation of Brief Homage to Pluto and Other Poems by Fabio Pusterla (Princeton University Press, 2023). The award is sponsored by The John D. Calandra Italian American Institute in New York City and the Journal of Italian Translation.

Originally from New York City, Professor Will Schutt holds a B.A. from Oberlin College (Ohio) in Creative Writing and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Hollins University in Virginia. He is the author of Westerly (Yale University Press, 2013) and translator of several works of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction from Italian, including Brief Homage to Pluto and Other Poems by Fabio Pusterla and My Life, I Lapped It Up: Selected Poems of Edoardo Sanguineti (Oberlin College Press, 2018). His work has been recognized with numerous awards, including the National Endowment for the Arts Literature Translation Fellowship and the Raiziss/de Palchi Translation Award from the Academy of American Poets. In Fall 2024, he is teaching two Creative Writing Workshops: Mixed Genre and Poetry.

Professor Schutt, who started teaching at JCU in 2023, was recently interviewed by Professor Berenice Cocciolillo, who teaches Introduction to Professional Translation at JCU.

Congratulations on winning the 2024 Joseph Tusiani Italian Translation prize in September 2024 for your translation of Brief Homage to Pluto and Other Poems, by Fabio Pusterla. What are the main challenges of translating poetry and this book in particular?

Thank you. I’m honored and humbled by the prize, and glad to have another excuse to draw attention to Fabio Pusterla’s poetry—some of the best being written in Italy right now. I think the challenges of translating poetry are several, and usually only a few of them can be taken up at a time. It’s important for someone translating poetry to consider how a poem is acting like a poem—what music it’s making, what patterns it’s weaving, how it’s playing with language. For me, it’s a process of considering how to carry over a poem’s form, rhythm, the little melody of vowels and consonants it makes, as well as the connotative, resonant meanings that the lines accrue as the poem meanders down the page. But I suppose—formal constraints aside—that is true of any literary translator for whom style and meaning are closely intertwined. Pusterla is a lyric poet, and by lyric poet I mean someone interested in the aural properties of language; in generating a text that is half-spoken, half-sung; in questions of the self and the self’s relation to others. In his poems I can hear a human voice—or voices—and making that audible to readers is a challenge, yes, but also what makes translating him interesting to me.

What’s the relationship between Will Schutt the poet and Will Schutt the translator? What do you think makes someone a good translator?

I don’t always draw a distinction between the two, especially when I’m translating poetry. In both cases, I’m writing, searching for the right words, order, and formulations. That said, when I’m translating, I am generally more conscious about the degree to which the English sounds “natural” or “organic,” given the stiffness or obscurity often associated with translated works. Unless, of course, the original is deliberately opaque, stiff, strange, etc. (There’s another challenge of literary translation: literary authors are usually using language in idiosyncratic ways.) One major difference is that when I’m writing my own poems there’s nobody else in the room. I have to generate my own voice and my own subjects. I have to face the blank page—and myself. It’s a far more vulnerable position to put yourself in, to say what you have to say, and in public, and for posterity. That may explain why translator me is far more prolific than poet me.

As for what makes a good translator, I guess there are various qualities a translator should possess. The attentiveness of a close reader and ear of a good writer. Nerviness. A love of language. Admiration (ideally) for the authors they translate. Or at least respect. Some sense of the context out of which the original work has emerged, or the curiosity to learn more about that context.

As a professor of creative writing, what is your teaching philosophy?

I see my job as turning students’ attention to things that sometimes get lost in the classroom of Big Ideas and Historical Contexts—to the well-crafted sentence, to the memorable metaphor. Not that context and meaning are unimportant, but they can overwhelm what I assume made a young writer want to write in the first place: excitement about what words can do. I often ask my students to ride the surface of a text, in addition to mining it for meaning, with the hope that they’ll appreciate, say, the transformative power of a line break, or a well-placed comma. A writer is a reader. That statement sounds obvious but bears repeating. So, in my classes, we read stories and poems and essays, and I hope that among those readings students will find something that casts a spell over them, and from which we can learn together, by examining the way in which that thing is made, how to cast our own spells on the page.

What tips and/or advice would you give to aspiring writers/translators?

Part of me suddenly wants to be realistic about things, especially if we’re talking about poets and translators of poetry, and to say if you can do anything else, do that! Neither profession is paid much more than lip service by mainstream culture. Poets and translators exist on the margins of society. When Shelley says poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world, the stress is on the word “unacknowledged.” Writing and translating require many nights, weekends, and holidays alone.

And yet another part of me wants to enumerate the rewards. Writing and translating are nourishing in ways that are hard to define, but palpable, and some of their power derives from their existing on the margins. And some of their power derives from their being performed alone on nights and weekends. They teach you, for one, how to be alone.

But let me lighten up. The German writer W. G. Sebald once said that literature is play for high stakes. With that in mind, I’d encourage young writers to play, to experiment with styles and forms, to see writing as an act of discovering what you have to say in the process of saying it. That process is messy, yes, but of the romp-through-the-woods variety.

As for aspiring translators, well, I remember years ago hearing the poet and translator Brian Henry describe translation as a form of friendship. With a text, with an author. That always seemed illuminating to me, a healthy way to view the work of a translator. I guess that takes us back to my point about being alone. You aren’t. The works and words you translate are your company. They sustain you.

What projects are you currently working on?

Having recently moved to Rome, I’ve been getting to know the city by translating poems by poets from the city or who have called the city home: Patrizia Cavalli, Valerio Magrelli, Leonardo Sinisgalli, among others. I don’t have a particular translation project in mind, though at some point in the future, I envision gathering my various translations into a book, something like Eugenio Montale’s quaderno or Tom Paulin’s wonderful Road to Inver. I’m also finishing up a second manuscript of poems and spent much of the summer keeping a short prose diary about daily visits to the Giardino degli Aranci (Orange Garden), near where I live. What I’ll do with that I don’t quite know yet. As I said, it’s a messy process.