A Riveder le Stelle: Dante in the 21st Century

On April 7, 2021, JCU’s Modern Languages and Literature Department and English Language and Literature Department hosted the online event “Dante in the 21st Century.” The event was organized on the occasion of the 700th anniversary of poet Dante Alighieri’s death (1265-1321). The speakers were Italian Studies Professor James Schwarten, History Professor Fabrizio Conti, and English Professor Allison Grimaldi-Donahue.

Professor Schwarten kicked off the event with a presentation titled “Teaching the Divine Comedy in 2021: Challenges, Delights, and Revelations.” He discussed insights and perspectives that emerged from his classes at JCU, where he has been teaching the Divine Comedy since 2016. Among the challenges that Professor Schwarten mentioned is the fact that multiple translations of the Divine Comedy present different ways to read and understand the poem. Therefore, despite Schwarten choosing a specific translation for his classes, some students ended up buying cheaper versions of the poem, which made references and readings challenging.

Fortunately, according to Professor Schwarten, the accessibility of resources on Dante facilitates teaching the poem. Columbia University’s Digital Dante, or The University of Texas at Austin’s Danteworlds, for example, are very good resources for interactive pair or group work. In discussing Dante’s significance today, Professor Schwarten called attention to the fact that the medieval poet is even referenced in popular culture. Among the examples he mentioned were a campaign to reduce water consumption, an ice cream advertisement, a comic strip, and a t-shirt that defined laundry as “Dante’s lesser-known Tenth Circle of Hell.”

Professor Schwarten concluded his presentation by saying that in the Divine Comedy, Dante touches on themes that are still relevant today, such as the notion of justice, the sense of reward and punishment for doing right and wrong, how to deal with corruption, or the difficulties one might encounter when trying to reach personal happiness. But Professor Schwarten also conveyed a sense of hope as we follow Dante’s journey “out of the dark woods and into the light.”

Professor Conti gave the presentation “The World and the Heavens: Magic and Astrology in Dante and in His Own Time.” He began with an overview of Dante’s life and the unrest that characterized Florence due to the rivalry between two opposing political factions, namely the Guelphs who supported the Pope, and the Ghibellines who supported the Holy Roman Emperor. Dante was deeply engaged in political events, and he participated in the 1289 Battle of Campaldino, Tuscany, between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. Dante was among the Guelphs, who were victorious, but by 1300 they had split between Whites and Blacks. The Blacks continued to support the Papacy, while the Whites had a more moderate view of Papal influence. Dante belonged to the White Guelphs faction, and when the Blacks took over Florence, he was exiled for life in 1302.

According to Professor Conti, magic and astrology were heavily debated in Dante’s time. He places astrologers and diviners in Inferno’s 8th circle (Malebolge), and he describes them as having their heads facing backwards. Being deprived of the ability to see in front of them, astrologers and diviners were condemned to walk backwards. Among the people that Dante meets are Michael Scot, astrologer of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II; Guido Bonatti, one of the most popular astrologers of his time; Asdente or Maestro Benvenuto, shoemaker and astrologer. Dante also places in Inferno a sorceress such as Virgil’s Manto, and a number of unnamed female witches, and he also mentions Lucan’s sorceress Erichtho. Professor Conti concluded with the image of Dante who, having passed through hell and purgatory, from the heights of the heaven of the fixed stars turns and smiles down on the Earth.

Professor Grimaldi-Donahue presented “Dante the Contemporary Poet: Ciaran Carson and Mary Jo Bang Translating Inferno.” She explained that “translation liberates students and allows them to try on new voices, while teaching them the architecture of literature from the inside out.” Professor Grimaldi-Donahue’s interest in translations of the Divine Comedy was sparked by poet Caroline Bergvall’s Via, a variation piece based on 47 translations into English of Dante’s opening lines of The Inferno. Via inspired her to connect Dante and creative writing, and to use translation as a tool for refining this skill.

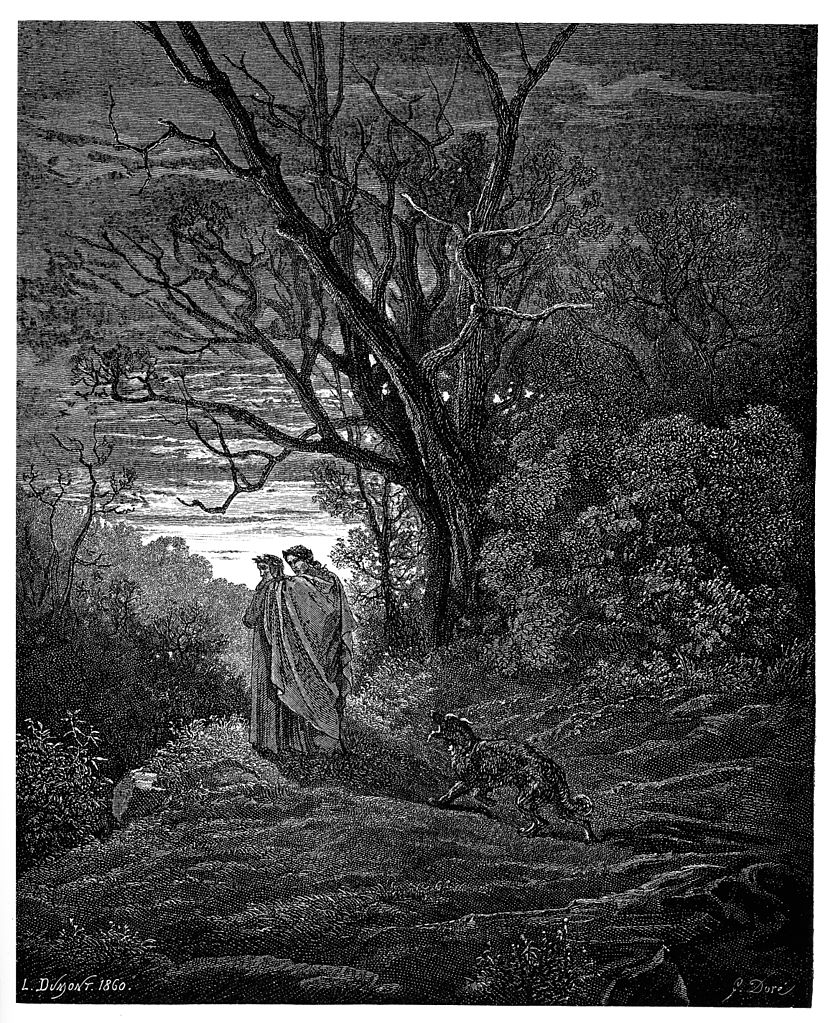

Gustave Doré – Inferno

Professor Grimaldi-Donahue also explored the reason why there are so many translations of Dante’s Divine Comedy and wondered if it is “blasphemous to mess with a master.” She quoted Walter Benjamin’s 1923 essay The Task of the Translator. Benjamin says “for a translation comes later than the original, and since the important works of world literature never find their chosen translators at the time of their origin, their translation marks their stage of continued life. The idea of life and afterlife in works of art should be regarded with an entirely unmetaphorical objectivity.”

Professor Grimaldi-Donahue said that a translation can come hundreds of years after the work is created, bringing it into a new time, and making it available to a new set of readers. This means that the best translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy might not exist yet. She added that translations recreate and reinterpret the original work, giving it a new life. The first complete American translation was done by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) in 1867. Since then, the poem has been translated and published, in part or as a whole, over 100 times.

For her analysis, Professor Grimaldi-Donahue considered the translations by American poet Mary Jo Bang (b. 1946), and Irish poet and novelist Ciaran Carson (1948-2019). Some of the formal differences between their translations of the Divine Comedy are the fact that Carson creates a song-like poem, whereas Bang uses internal rhyme and other devices like alliteration and assonance. Moreover, Carson inserts his own culture primarily through sound, and Bang does so through references and homages. Carson seeks to modernize the religious allegory, and Bang to transcend it.

Professor Grimaldi-Donahue concluded that different translations of ancient texts keep them alive and make them less “precious.” They become poems we can live with and through, which become part of our own culture, language and experience. “In translating them we become like the poets we most admire, even just a little bit. We learn to play with language again, take our guard down about sharing work, experiment with new forms, and get to know new cultures and histories,” she said.

About the Speakers

James Schwarten, lecturer in Italian and Italian Studies, has research interests in Italian language and literature, translation, and sociology. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His teaching interests include Italian literature and sociology. He edited Vincenzo Patanè’s The Sour Fruit: Lord Byron, Love & Sex (Translated by John Francis Phillimore, Roma: John Cabot University Press, 2018) and translated Dacia Maraini’s Extravagance and Three Other Plays (Lanham, MD: John Cabot University Press, 2015.)

Fabrizio Conti received a dual Ph.D. in History and Medieval Studies from the Central European University, Budapest (Hungary). He is a graduate in the Humanities from the University of Rome “La Sapienza,” and has earned certificates from the Pontifical Institute for Christian Archaeology in Rome and the School of the Vatican Secret Archive. His teaching and research interests span the Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance periods, with an interdisciplinary approach to intellectual, social, and religious developments. His book entitled Witchcraft, Superstition, and Observant Franciscan Preachers: Pastoral Approach and Intellectual Debate in Renaissance Milan was published by Brepols in 2015, and his edited book Civilizations of the Supernatural: Witchcraft, Ritual, and Religious Experience in Late Antique, Medieval, and Renaissance Traditions, with a foreword by Teofilo F. Ruiz, was published by Trivent in 2020.

Allison Grimaldi-Donahue is an educator, writer, translator, and editor. Her work has appeared in Words Without Borders, The Brooklyn Rail, Electric Literature, Arkansas International, Prairie Schooner, Flash Art, and NERO among others. She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Critical Thought at the European Graduate School with a thesis on translation theory. She is a regular presenter at the annual American Literary Translators’ Conference. This past year she was an artist in residence at MAMbo, Museum of Modern Art Bologna. Her translation of Carla Lonzi’s Autoritratto will be published in September 2021 with Divided Publishing, London.

Watch the video of “Dante in the 21st Century”